China 25.09.2017 TransIndus

In the year 139 BC, the Han Emperor Wudi dispatched his top diplomat, Zhang Qian, on a mission to the unknown kingdoms west of the Great Wall. Braving some of the most extreme weather and wild nomadic peoples in Asia, he left at the head of a caravan of 99 men, returning 13 years later with only one. Yet despite the loss of his entire expedition, Zhang Qian was garlanded as a great explorer. For his accounts of the distant lands beyond the deserts and vast mountain ranges of the far west came as a revelation, opening up connections with the world beyond the borders of ancient China that would transform the lives of millions across the globe.

It was via the chain of oases leading across the deserts – known apocryphally as the ‘Silk Road’ – that Buddhism first reached the Yellow River, along with walnuts, grapes, wine and glass. In the other direction, gunpowder, oranges, roses, paper, knowledge of printing and, of course, silk making were among the wonders exported to the western world.

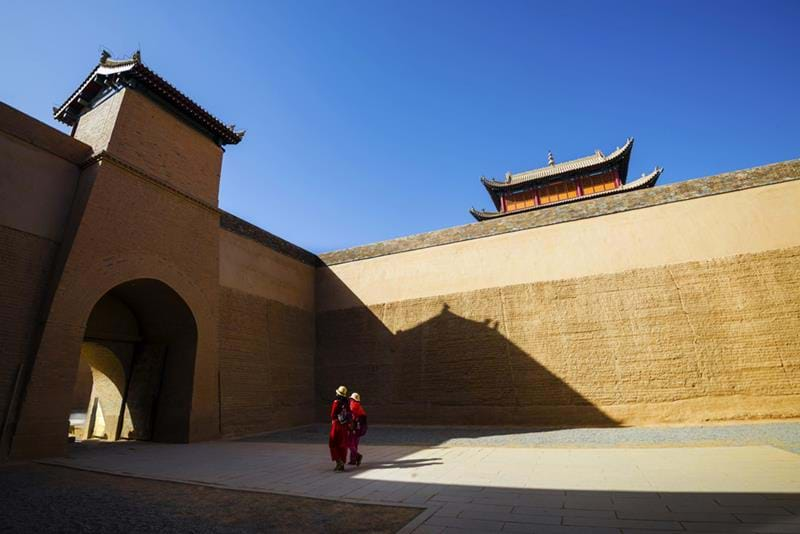

In time, the Chinese emperors erected a chain of forts along the old trade routes. Funded by profits from the commerce, monastic complexes also appeared, hewn from sand-blasted loess cliffs and richly decorated inside with murals and sculpture. Libraries of precious manuscripts and banners were also amassed, recording the earliest eras of Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity and the all-but-forgotten Manichaeism faith.

These evocative religious monuments, along with the remains of the great market hubs that once dominated the Silk Road, form the stepping stones of modern journeys across the provinces of Gansu and Xinjiang. It used to take 5 months to travel between Xi’an and Kashgar in the far west, crossing the mighty Taklamakan Desert to the passes that led over the Tianshan, Kunlun and Karakorum ranges into Central Asia and India. These days, thanks to modern air travel and land cruisers, you can cover the highlights in a couple of unforgettable weeks – and, unlike the hardy traders of past centuries, in great comfort, too.

In 2014, UNESCO highlighted the importance to world history of the Silk Road and associated monuments with its inauguration of the Chang’an–Tianshan Corridor, a 3,000-mile (5,000-km) sequence of cities, palace complexes, trading posts, cave temples, ancient pathways, beacon towers, tombs, guard posts and sections of the Great Wall. Its twin starting points are the former capitals of the Chinese dynasties whose patronage fuelled the rise of the Silk Road: Chang’an (Xian) and Luoyang in Shanxi Province – pivotal points on our own preferred routes through the heartland of China, and the perfect launch pads for extended journeys along this legendary trade artery.