Oman 03.05.2019 David Abram

Author David Abram traces an ancient trade route along the coast of Oman

It has to be the most evocative perfume on the planet. One whiff and I’m immediately transported, in high Proustian fashion, to a gloomy chapel in the mountains of Crete. Or to the afternoon in Corsica when I once stumbled on a polyphony trio practicing in a deserted cathedral, watched by doleful ranks of Delacroix portraits.

It is mentioned repeatedly in the Old Testament and the Talmud; was prized by the Pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom, and has even been found in tombs of Ming emperors.

Now I was standing in front of sack load of it, piled into fragrant, amber-coloured heaps. ‘This frankincense!’ announced the stall holder. ‘In the time of the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him), more valuable than gold!’

He’d clearly done his homework. Scooping and sprinkling bowlfuls of the granules as he spoke, the vendor told me how trade in the incense had fuelled the rise of wealthy ports on the eastern shores of the Arabian Peninsula, drawing merchants’ ships from Rome and the Far East.

‘Now too much cheap! Come, sit . . .’

The stall was buried deep in the bowels of Muttrah Souq, just around the headland from Muscat, the modern capital of Oman. Muttrah is a port with much older roots than most of its cousins elsewhere in the Gulf. And these are nowhere more discernible than its wonderful covered market, where Sheikhs sporting the latest iPhones rub shoulders with craggy-faced Bedu from the Rub al Khali desert, and pomegranate farmers from the wadis of the Jebel Akdhar shop for wedding jewellery in glittering, mirror-lined emporia.

‘This number one quality. From Wadi Dawkah!’.

The frankincense seller explained how, for thousands of years, most of the world’s supply came from a single valley in the far south of Oman’s Dhofar province, sandwiched between the vast expanse of the Empty Quarter and the Arabian Sea. Its source was a rare tree, Boswellia sacra, which thrived in the unique micro-climate of Dhofar’s interior.

‘In July month monsoon rain arrive, the ‘Khareef’. Yes, sir. Here only! For three month heeeeavy rain. Wadi becomes fully green. Frankincense tree they drink!’

As the heat of the Arabian desert reaches its seasonal peak in mid-summer, humid air is drawn in from the ocean to the coast, falling as rain when the clouds run into the wall of mountains inland.

In March, the trunks of the Boswellias are scored and the crystallized sap collected. Camels would carry it north across the desert to the Red Sea, and northeast to the sea port of ‘Khor Rori’, aka ‘Sumhuram’, to which ships from the Malabar and China would for many centuries come to trade.

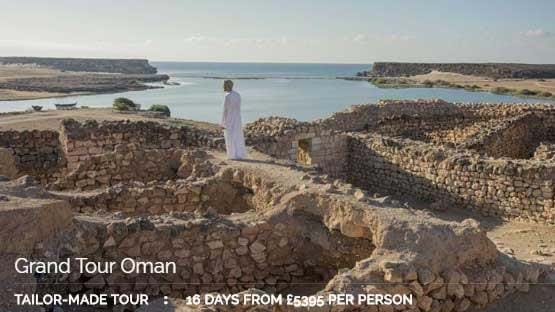

A couple of days after my visit to Muttrah Souq, I visited the ruins of the ancient port, half an hour’s drive east of Oman’s second city, Salalah. It sits on an isthmus of land dividing a fresh-water lake from a beautiful, shell-shaped bay. From around the 4th century BC until the 5th century AD, this perfect natural harbour was among the most prosperous in the world thanks to the sap from Wadi Dawkah’s secret trees.

After tracing the outlines of streets, warehouses, tombs and temples at the site, I was keen to see for myself where, precisely, the money that financed the construction of this long lost city originated, and decided to book a guide for a drive north into the mountains.

They rose sheer from the coastal plain of Dhofar, their flanks eroded into giant ripples that were carpeted at lower levels by dense green vegetation – a rare spectacle in this ultra-arid part of the world.

‘Here, yes, this is Boswellia sacra’ my guide Suleiman confirmed, pointing to stands of low-slung, umbrella-shaped trees at the roadside. Gradually, as we gained altitude, their numbers increased, eventually forming a blanket of unbroken green over the slopes.

We stepped out of the car and Suleiman reached into his pocket for the small Omani khanjar he carried expressly for this purpose. Scraping away a flake of bark with the point of his blade he gouged loose a globule of dried sap and passed me the knife.

‘The frankincense farmers they call this ‘tears of the tree’’.

The scent was less intense, but unmistakable. I closed my eyes, drew in a noseful and found myself momentarily back in Bastia cathedral, the harmonies of those ethereal Corsican hymns mingling with the mysterious, aromatic smoke that curled from the brazier beside the altar.

Find out how you can tie the places featured in this article into a wider-ranging tour of Oman’s scenic and cultural highlights by clicking >>Grand Tour Oman or the picture below.....