India 14.03.2018 David Abram

Travel writer, David Abram, revisits the ruined city of Mandu in central India, and recalls the extraordinary tale of how two travellers from Jacobean England crossed paths here in 1617 . . .

It’s been a while – a whole quarter of a century in fact – since my first visit to Mandu. The Archeological Survey people have added a few lawns and spruced up some of the buildings. There are flower beds now. And a couple of interpretative panels. But I’m happy to note that the rugged, remote, eerie splendour of this ruined Muslim capital on the northern rim of the Deccan Plateau remains undiminished.

Stepping out of my car after a two-hour drive from Indore airport, I’m struck by the monumental scale of the place. Everything is much grander than I remember: the towering walls of the sultans’ palaces; the corridors of immaculately dressed stone; the cloisters of the Jama Masjid, inspired by those of the Great Mosque in Damascus; the sensuous curves of the bathing pools in the zenana, where a harem of some 15,000 women were guarded in sumptuous luxury by a thousand female Abyssinian warriors.

With their onion-domed cupolas and bands of Persian calligraphy, Mandu’s monuments are superbly exotic to the foreign eye. But for me, it’s the ghosts swirling around them – the half-remembered histories of people who inhabited these beautiful buildings in past centuries – that make this such a special site.

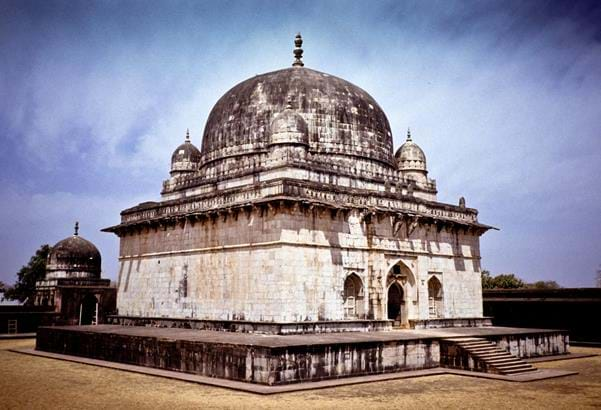

The fortress-town served as the capital of a dynasty descended from the Afghan warlord Dilwar Khan, who carved out a kingdom for himself after Timur’s destruction of Delhi in 1498. His son, Hoshang Shah, was responsible for the most splendid of Mandu’s monuments, chief among them his own white marble tomb (allegedly an inspiration for the architects of the Taj Mahal).

Leaving Mandu’s royal palace complex behind me, I walk south, following a lane across a tract of undulating, rocky scrub dotted with baobab trees and crumbling Afghan tombs. A colony of bats are streaming from the arched entrance to one of these as I climb its steps.

It might well have been in this very tomb that the first British Ambassador to India, Sir Thomas Roe, camped in July 1617, while attending the court of Emperor Jehangir. The Great Mughal sometimes spent the monsoon months here, and the fledgling East India Company had sent Roe to secure trade privileges.

While he was here, grappling with political intrigues and nocturnal attacks by ‘lions and wolfes’, Roe crossed paths with the English travel writer, Thomas Coryat, who had walked all the way to India from Somerset.

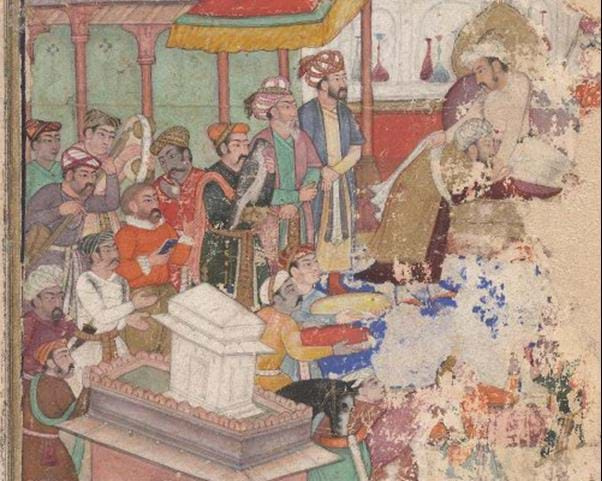

Sir Thomas Roe (left of picture, wearing orange) at the court of the Mughal emperor Jehangir in 1617

Wouldn’t you love to have been a fly on the wall as the ragged mendicant Coryat – penniless and dressed as a fakir – introduced himself to the sumptuously attired emissary of King James I? This was the Stanley-Livingstone moment of early English travels in the subcontinent, yet no description of the meeting has survived. Roe’s diary merely mentions it in passing, while Coryat’s memoirs were lost before he could commit them to print.

Both men, though, would certainly have visited the pretty palace complex crowning the farthest, southern lip of the Mandu plateau, whose upper terrace affords a wondrous view over the Narmada Valley. A flock of green parakeets screech past as I emerge from the stairwell on to the raised walkway, its flagstones warmed by the afternoon sun.

According to local legend, this serene structure was built by Sultan Baz Bahadur for a beautiful goatherd called Roopmati, whom he encountered while out hunting one day. She only agreed to marry him on condition he construct a palace for her overlooking the river, and it was here, years later, with the army of Mughal Emperor Akbar about to breach the city’s defences, that she eventually took her own life – by eating crushed diamonds.

As I try to picture the scene, the sun is sinking into the haze of the western horizon. Shepherds are calling to their flocks on the hillside below, and pall of smoke from cooking fires hangs over the nearby Bhil village. It’s a view that would have been recognizable to Coryat and Roe who, I like to imagine, might well have stood at this exact spot nearly four centuries ago, contemplating the long journey downriver to Bharuch or Surat, and onwards by sea to re-join their respective families back in ‘Merrye England’.

Roe would go on to become the MP for Cirencester and pursue an illustrious career as a diplomat. Coryat, alas, fared less well. Laid low by dysentery and the overbearing hospitality of drunken English traders in Surat, he died before he could board a ship home.