Uzbekistan 07.11.2019 Amrit Singh

Among the members of the group tour, I recently led to Uzbekistan was a Jewish couple from north London who, when we arrived in Bukhara, asked if we might arrange a visit to the local synagogue. A former Soviet Republic stretching across the deserts of Central Asia, Uzbekistan is a predominantly Muslim country, so it is surprising to find that this ancient city has a Jewish place of worship.

“Oh yes,” our local guide explained, “there was indeed a large Jewish community but not many remain”. He was able to re-jig the day’s programme to include the old synagogue. The rest of the group were intrigued and joined the visit the following day.

Hidden down a side street just off Bukhara’s main square, the 300-year-old building was surrounded by a mud-brick wall pierced by a small door in a more substantial gateway. A small signboard dangling outside was the only clue to its existence.

Our group was warmly welcomed inside by Abraham Ishakov, a local historian and president of the Bukhara Jewish Community who helps care for the synagogue, the adjacent Jewish primary school and the nearby cemetery, where around 10,000 Jewish graves reside.

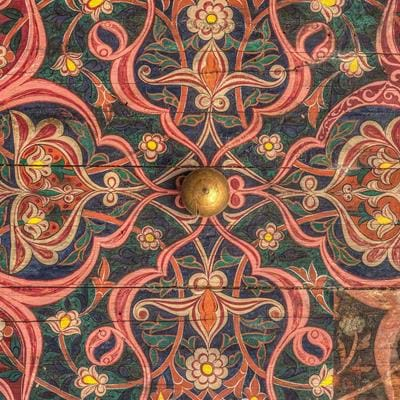

We were led through a beautifully tiled courtyard into the first of two resplendent prayer rooms. Abraham gave us a brief introduction to the Jewish community in Bukhara, explaining how Jews had settled here many centuries ago – possibly as long ago as the sixth century BC, following the Persian sack of Babylon by Cyrus the Great. In Timurid times they flourished as bankers and merchants; around 45,000 remained under Soviet rule, but when the newly independent Uzbek government relaxed emigration laws in the 90s, all but a handful left for Israel and New York, fearful of persecution in the new Muslim country (fears that were ill-founded, as it turned out).

“There are currently around 50,000 Bukhari Jews in the borough of Queens, New York, but less than one hundred here!” said Abraham, as he explained the significance of the decorations and inscriptions emblazoned on the walls. “These days, we rarely find a ‘minya’ (a quorum of ten) to hold a service. And there are only four or five families who keep kosher. The surviving Rabbis are too old and frail to wield a butcher’s knife” he said ruefully. “But when members of the diaspora return we are able to read from our most prized possession, a Torah dating back to the reign of King David!”

Abraham jumped to his feet and ushered us into the second prayer room where he unlocked a glass cabinet containing a magnificent scroll wrapped in beautifully embroidered silk suzanis.

“We don't show this to everyone, but you are our most honoured guests,” he says, bowing his head slightly.

As the group gathered around the hallowed scroll for a photo, Abraham sang an old Hebrew blessing in a beautiful baritone voice – a melancholy experience that will remain with us all.

“But what about the children?” asked one of the group once the singing has finished.

“Ah yes. Well, the school next door currently has 440 pupils. However, only a handful of them are Jewish. The others attend because of its excellent academic reputation. Our hope is that our non-Jewish students will one day act as our inter-faith ambassadors.”

Sadly, the lure of more vibrant, thriving Bukhari communities overseas, coupled with the paucity of people of marriageable age, mean this particular thread of Central Asia may unravel over the coming decades. “Soon this building will be all that is left to remind the world that we were here . . .” said Abraham out in the courtyard, smiling gently as he closed the old Bukhari door behind us.

If you’d like to visit the beautiful synagogue in Bukhara as part of a group tour or tailor-made tour, please contact our team of specialists and they will be to help you plan your next trip.