Uzbekistan 19.05.2016 David Abram

In our follow-up piece on the sites featured in Sam Willis’ BBC4 documentary, Silk Road, David Abram marvels at the splendour of Uzbekistan.

The second instalment of Silk Road soared like a Sogdian ‘Heavenly Horse’ from the Deserts of Xinjiang, over the Tian Shan Mountains and east across the grasslands and serrated ridges of Kyrgyzstan to Uzbekistan.

Sam Willis entered the former Soviet Republic at Tashkent, the nation’s capital, then took a train onwards to the city of Samarkand, where Tamerlane (aka ‘Emir Timur’) and his descendants erected Central Asia’s greatest horde of monuments. From there, he continued on to the equally splendid cities of Bukhara and Khiva – a route mirrored by our fabulous, 3-week tour of the region’s cultural highlights, Legends of the Silk Road.

Samarkand

Encircled by snow-lit mountains, the exquisitely symmetrical domes and minarets of Samarkand have been the marvel of the Silk Road for over a thousand years. And although they are these days hemmed in by bleak Soviet-style conurbation, the city still has about it an aura of near mythic remoteness.

Foremost among the surviving monuments here is the Registan, a grand square where Sam Willis marvelled at the azure-, turquoise- and yellow-tile-encrusted facades of huge madrasas and minarets. Nearby, the resplendent Bibi-Khanym mosque has a brilliance compared by poets over the centuries with that of the Milky Way.

Narrow alleyways lined with mud-walled courtyard houses make up most of Samarkand’s Old Town, where Sam soaked up the traditional sights and sounds of the street markets and bakeries. One of the highlights of the programme was his visit to a traditional tile workshop, where artisans fashion the pieces used to renovate the elaborate mosaics on the Registan.

Sam also visited the fabulous Afrosiab Museum, near the Bibi-Khanym mosque, in which are preserved exquisite murals dating from the 7th and 8th centuries, when the region was ruled by the Sogdians. They show dignitaries visiting from China, India, Iran and Turkey and are unique in the world.

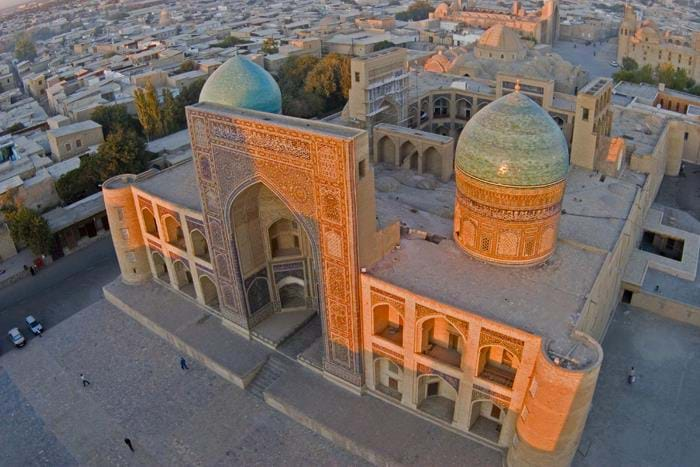

Bukhara

The chimeric monuments of Bukhara were mostly erected by the descendant of Timur, and by the Uzbek Shaybanid dynasty who succeeded them in the 16th century. In recent years, a huge amount of work has been carried out by the Uzbek government to restore its greatest landmarks to their former glory, and although the sprawling Poi-i-Kalan complex, Laub-i-Hauz ensemble and other sites in the centre look a touch too clean these days, they still ooze grandeur and mysticism.

In the northwest of the old walled city, the Ark is a vast palace-fortress associated with the darker side of the regimes who ruled the city from the 5th century AD until the flight of the last Emir in 1920. Sam Willis skimmed over the unfortunate episode for which the fort is infamous among British historians: in 1842, two emissaries of the East India Company, Stoddart and Conolly, were beheaded inside the Ark for not bringing suitable gifts for Nasrullah Khan!

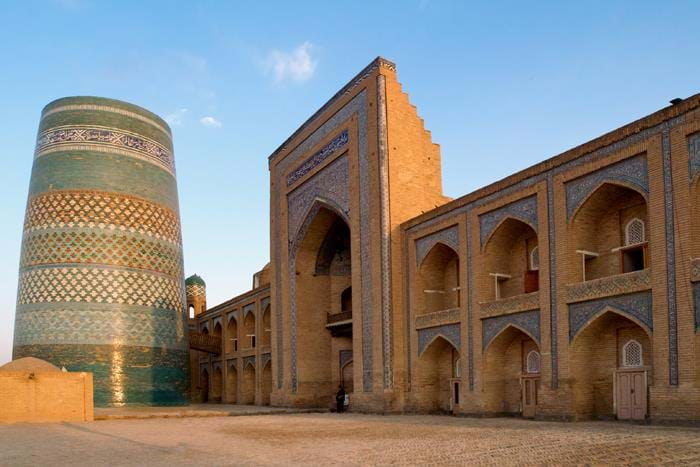

Khiva

In the early 19th century, the name ‘Khiva’ was no less feared by Western explorers. The capital of a famously sadistic despots known as the ‘Khans’ (direct descendants of the redoubtable Gengis Khan), it served as the final staging post for caravans bound across the desert to Iran. Evidence of Khiva’s former prominence is an exceptional ensemble of monuments, whose jade-green and blue-glazed domes soar above belt of medieval mud walls. Most have been immaculately restored, yet they attract far less attention than those of either Samarkand or Bukhara.

The defining landmark here is the Djuma mosque, whose brick domes are supported by pillars that were originally carved from black elm and apricot wood more than a thousand years ago, when Zoroastrianism still held sway in the region.

Wood carving is still very much alive and well here, and we recommend that while in Khiva TransIndus clients follow in Sam’s footsteps and pay a visit to the wonderful workshop of Shavkat Tumaniyazov, where traditional Khivan designs dating from the 10th century are still sculpted from local timber. The workshop was featured in its own delightful documentary, which you can watch on the BBC iPlayer.